ABOVE: Dressed in their Sunday best, local kids relax on the lawn of the former Seaside Hotel in Waikiki.

There's a street in Waikiki named Seaside Avenue, which does its best to keep alive the memory of its namesake, a once-loved Honolulu institution called the Seaside Hotel. A century has passed since the Seaside's last guests checked out and bulldozers rolled in to clear the way for the much grander Royal Hawaiian Hotel. The Royal Hawaiian is going strong, but the Seaside—despite Seaside Avenue's efforts—is long forgotten. In its day, though, the Seaside was a world-renowned resort and a local hot spot where townsfolk flocked for fun.

When the hotel opened in 1899, Waikiki was still out in the country, with more mosquitoes than people and duck ponds everywhere but not a single ABC Store. Farm shacks, rice paddies, loi kalo (taro patches) and banana groves abounded inland, while stately beach homes and a few public bathhouses lined the shore. People traveled by horse-drawn vehicle or aboard the electric trolley. The crowing of roosters and the odor of pigs rode on the trade winds.

By the time the Seaside's lease expired in 1925, the creation of the Ala Wai Canal had diverted Waikiki's streams, drying up the wetlands and driving off the farmers. Housing tracts were springing up all around, and automobiles zoomed along newly carved streets. More visitors were coming to Hawaii than ever, and Waikiki had outgrown what the quaint, turn-of-the-century Seaside could provide.

Little has been written about the Seaside since it disappeared from Waikiki Beach one hundred years ago, but a chronicle of its lively quarter-century run can be found in thousands of contemporaneous newspaper items. I went down that rabbit hole while working on a book about the stories behind Waikiki's street names, a project riddled with rabbit holes. I wasn't expecting to find much behind Seaside Avenue's prosaic name, but boy, was I wrong. And boy, did I spend too much time burrowing into the newspaper archives and poring over historic photos, guest narratives and fire insurance maps. I came away with an image of the Seaside Hotel as an idyllic place unlike anything seen in Waikiki since—a rustic forerunner to the clamorous high-rise hotel district of today, a deep breath before the onrush of modern Hawaii.

Island residents went there for beach access, concerts, "jolly Saturday evening dances" and special occasions of all sorts. Visitors found many of the same things that delight Waikiki's visitors today: hula, surfing, luau, Hawaiian music, outrigger canoe rides, contemplating Diamond Head while lounging beneath a hau tree with a cocktail in hand. The hotel even pioneered Waikiki's fireworks shows—or tried, anyway.

In the summer of 1907 the management announced plans to launch Roman candles, "giant rockets" and other pyrotechnic devices from outrigger canoes riding toward shore in the dark. This drew an extra-large crowd to one of the jolly Saturday evening dances. "Unfortunately," as the Hawaiian Star reported, "heavy surf filled the canoes, wetting the fireworks so that the display was not the success that had been hoped. ... Everyone had a thoroughly good time, however."

From 1899 until 1925, the Seaside Hotel on Waikiki Beach catered to guests from faraway places and townspeople alike. Above: Beachgoers look seaward beside the hotel's bathhouse, with its two-story lanai extending over the water.

The Seaside was a cottage-style hotel, a patchwork of low buildings spread over nearly ten palm-shaded acres. It started out as the beach addition to a prominent downtown hotel, the original Royal Hawaiian Hotel, and was initially called the Hotel Annex. It was renamed in 1906 after striking out on its own. The owners held a naming contest, expecting someone to suggest Seaside Hotel. But nobody did, so they kept the $10 prize and went with the name they had in mind all along.

A historic coconut grove covered most of the property, with some massive kiawe (mesquite) trees dappling sunlight across the beachside lawn. Helumoa is the traditional name for the place, and for most of Hawaii's history it served as home for the island's ruling alii (chiefs). Part of King Kamehameha I's fearsome fleet of war canoes landed there during his conquest of Oahu, and Kamehameha made his residence there. For his descendants, down to Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, whose estate still owns the land, Helumoa served as a beach retreat.

The Seaside offered a rustic and slightly more affordable alternative to the palatial Moana Hotel, which opened in 1901, a short walk down the beach. Accommodations at the Seaside included some of the weathered shacks where royal retainers once slept, as well as some Victorian-style cottages the hotel built among the palms. At the beach edge of the property, built partly over the water, stood a boxy, two-story bathhouse. Painted red with a green hip roof, it was a conspicuous coastal landmark. The upstairs had rooms for single men; the downstairs had changing rooms, showers, lockers and bathing suit rentals. A wet early-twentieth-century bathing suit could weigh as much as a soaked blanket, so rentals were the norm.

A rambling one-story building housed the hotel's office, reception hall, kitchen, bar, private dining room and open-air dining lanai. This building had been there long before the hotel's time and was, apparently, the old royal beach house. The hotel added a spacious, semicircular dining lanai. With tables and chairs removed, and wax shavings sprinkled on the floor, the lanai doubled as a dance pavilion. Musicians set up beneath an adjacent hau tree arbor, alternating Hawaiian melodies with waltzes, reels, Tin Pan Alley hits or whatever else pleased the crowd.

The Seaside wasn't the only venue in Waikiki for "beach dances," but its dance pavilion was especially popular. "Open to the sea, swept by cool valley breezes, brilliantly illuminated, and with a perfect floor and entrancing music, no place in Honolulu can equal the pavilion as a ballroom," wrote the Pacific Commercial Advertiser in 1906. The contrast between the pavilion's warm glow and the many dark nooks and tete-a-tete corners tucked throughout the grounds added to the allure.

Many of the earliest dances were formal affairs attended by the military officers from the troop transport ships traveling between the West Coast and the Philippines in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. Honolulu high society turned out in force to mingle with the soldiers, who arrived in their dress whites, often accompanied by their regimental bands.

Dances grew more egalitarian as the century progressed. In the 1920s, when other big hotels announced in the newspapers their prohibitions on certain popular but provocative dances, the Seaside did not. Couples were free there, it seems, to dance cheek to cheek or do the shimmy without getting a tap on the shoulder from the management.

Accommodations at the Seaside included tent cabins, single rooms for men, weathered shacks from King Kamehameha V's time, and Queen Anne-style cottages built by the hotel. The old beach house that housed the hotel's reception area, office, bar and dining lanai, which doubled as a dance pavilion.

The Seaside was well suited for crowds. When townspeople headed en masse to Waikiki for a big event or holiday, they knew the Seaside would have refreshments, bathing suits, lockers to store their valuables and comfortable seating on the front lawn (sometimes called the sward). The Hawaiian Star described the moonlit scene of a brass band concert in 1904: "The wide lawns were covered with people of all ages and those who could not find seats on the sward, lined the little sea wall or took even more comfortable poses on the coral sands of the beach. The buildings and trees all sparkled with electric lights and when the moon passed above the threatening clouds the scene was not soon to be forgotten."

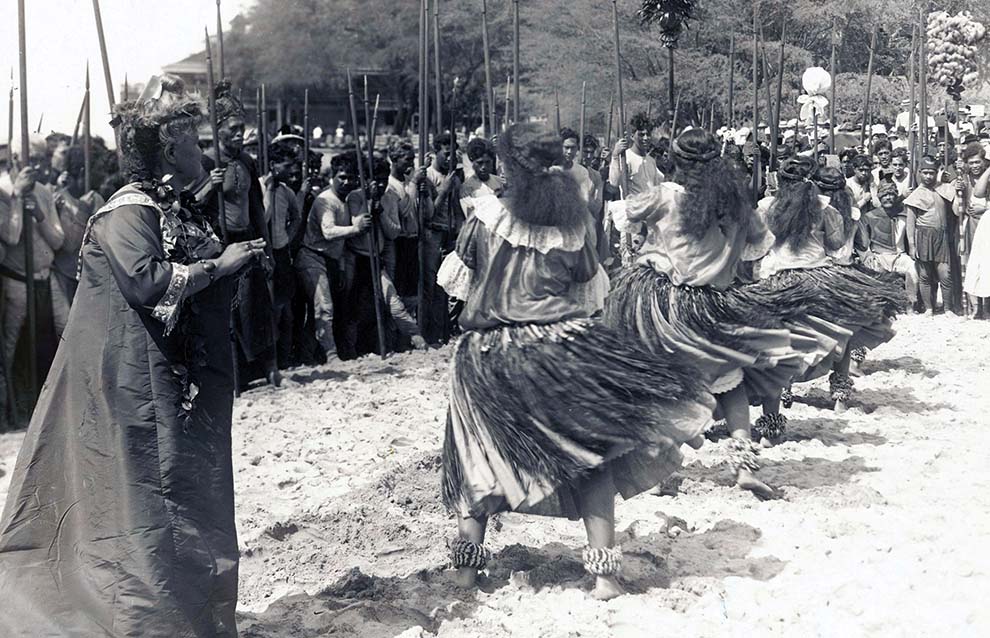

During the 1913 Mid-Pacific Carnival, when thousands of people jammed Waikiki Beach to watch a reenactment of the landing of Kamehameha and his warriors, the Seaside reserved the shady seating on its sward for women, offering them respite from the crush of spectators roasting in the sun. When Fort DeRussy test-fired an enormous fourteen-inch gun in 1914, hurling rounds at a target seven miles offshore, the Seaside invited everyone to witness the "spectacular military big-gun drill" from its grounds, free of charge.

When six hundred Shriners and their families swarmed Honolulu in 1911, the Seaside threw a luau. Honolulu Mayor Joseph Fern gave one of the opening speeches, addressing the fez-wearing crowd entirely in olelo Hawaii (the Hawaiian language). "He arose and spoke in his most fluent Hawaiian, his mother tongue," the Hawaiian Gazette reported. "The words spilled from his lips like honey and it seemed Mayor 'Joe' believed himself in the midst of a political gathering and that it was time to make votes." The good-natured Shriners couldn't understand a word, but they appreciated the sentiment and gave Fern a heartfelt round of applause.

The Seaside's manager then was Cecilia Arnold, who had once been part of Queen Emma Kalanikaumakaamano Kaleleonalani Naea Rooke's retinue and was a talented luau planner. The Shriners' luau was a small thing compared with the Seaside's 1909 luau for a visiting congressional delegation. A thousand invitations were issued, yet somehow eighteen hundred people showed up.

The bill of fare included twenty-seven pigs, fifteen hundred mullet, twenty-four large ulaula (red snapper), three hundred coconuts, thirty-five gallons of taro with coconut milk, twelve gallons of sweet potato and coconut juice, ten gallons of limu (seaweed), five gallons of wana (sea urchin), five gallons of boiled squid, two gallons of raw squid, five gallons of freshwater shrimp, twenty-four chickens, sixty cakes, eighty gallons of beer ... and more. Despite the enormous turnout, there were so many leftovers that hundreds of people returned the next morning to continue eating. "It was assuredly the star luau of local history," wrote the Hawaiian Star.

With the Seaside's bathhouse in the background, hula dancers and spear-wielding warriors took part in the 1913 reenactment of King Kamehameha I's landing at Waikiki, when his armies invaded Oahu in 1795. Thousands crowded the beach to watch. The Seaside sold refreshments and reserved the seating on its shady lawn for women.

Before air travel put Hawaii within a few hours of North America, the voyage by steamer from San Francisco took nearly a week, and vacations sometimes lasted for months. Newspapers kept tabs on the more illustrious visitors. "The Pillsburys and the Belles of Minneapolis, the great flour manufacturers, have engaged rooms and cottages at the Seaside hotel for six months," announced the Evening Bulletin in 1907, noting that the party was bringing its own "large touring car."

But some stays at the Seaside were all too brief, like the whirlwind visit of the "Montana Maids" in 1915. As winners of a popularity contest sponsored by the Butte Miner newspaper, twenty-one young Montana women embarked on a Western tour, with four days planned in Hawaii. Stormy weather put their ship in to Honolulu a day behind schedule, and upon arriving they declared a "strike," demanding more time in the Islands. "We were promised a six-weeks trip and we want to spend most of it in Hawaii to learn how to ride the surf boards," they cabled the newspaper.

But the Miner said no, so the women made the most of their abbreviated schedule, attending a ball, touring the Island in automobiles, sipping tea with the mayor and governor and getting lots of ocean time. Olympic swimming champion Duke Kahanamoku—famous then even in Big Sky Country—gave them swimming lessons, and they spent hours canoe surfing with the beach boys. "Talk about riding a cayuse," one told the Pacific Commercial Advertiser. "I shall never be content unless my saddle at home is fashioned after an outrigger canoe."

The Seaside's guests were forever mingling with members of the Outrigger Canoe Club, separated from the hotel by a picket fence, and Hui Nalu, the club of Hawaiian beach boys, which convened beneath a hau tree at the Moana Hotel. The Outrigger offered visitors temporary memberships for up to three months, and Hui Nalu provided surfing lessons, outrigger canoe surfing and an interface with Hawaiian ways.

Author Jack London stayed at the Seaside in 1907 in a tent cabin—another accommodation option—with his wife, Charmian, and spent two days learning to surf with the beach boys. On the third day he was too sunburned to get out of bed, so he stayed there and wrote his essay on surfing, "A Royal Sport"—"That's what it is, a royal sport for the natural kings of the earth," he wrote. Published in the widely circulated Ladies' Home Journal, the piece helped fix surfing in the American mind.

Another celebrity guest at the Seaside in 1907 was Alice Roosevelt Longworth, eldest daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt. For years the American public had been captivated by Alice, whose antics as an attention-starved child in the White House led a family friend to describe her as "a young wild animal that had been put into good clothes." She had grown into a refined young woman, albeit one whom Charmian London described as "refreshingly unbound by convention." At a time when women did not use tobacco, for instance, at least not publicly, Alice smoked up a storm wherever she pleased.

"We led a completely indolent existence in Honolulu," Alice later wrote, "in and out of the ocean all day and a good deal of the night." The two-story, shingled cottage where she stayed with her newlywed husband, the Ohio congressman Nicholas Longworth, henceforth became known as the Alice Roosevelt Longworth Cottage.

Years later, after Nicholas had become speaker of the House and the Seaside was no more, the Honolulu Mercury recalled an episode from the honeymoon. One night, as a Hawaiian quintet played beneath the hau arbor, and Alice "sat on the lawn apart from the throng and smoked cigarette after cigarette," Nicholas "edged within the charmed circle of musicians, smilingly took the violin from one of the players and at once began to use the bow with veteran skill." Amazed bystanders were soon on the floor dancing with abandon. "Old timers still ask whether it was Nicholas or the dancers who derived the greater enjoyment out of that unusual night at Waikiki."

Painted red with a green roof and well lit at night, the Seaside's bathhouse was a prominent landmark visible far from shore. By the time it was demolished in 1925 to make way for the construction of the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, it was about to collapse on its own.

By the time the Seaside was bulldozed in 1925, its old bathhouse looked like it might collapse on its own. The opening of the Royal Hawaiian in 1927, which practically doubled the number of hotel rooms in Waikiki, marked the beginning of a new era. Twelve hundred people attended the opening-night gala—not quite as many as the Seaside's 1909 mega-luau had drawn, but a good turnout. Between dinner and dancing, the crowd turned toward the sea to watch another reenactment of Kamehameha's landing at Waikiki.

"For a while the curtain of time was drawn back and there was revealed in resplendent color ... a living picture of ancient Hawaii," wrote the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. "Then the curtain dropped back into place. From somewhere in the distance came the strains of a fox trot, and, as the spectators moved toward the ballroom, modern Hawaii returned to claim her own."

A couple of weeks earlier, the street names for a new subdivision across Kalakaua Avenue from the Royal Hawaiian had been chosen: Royal Hawaiian Avenue and Seaside Avenue, which remain in use today. Some of the old Seaside's cottages had been hauled across the street to create a new hotel at the corner of Seaside and Kalakaua. It was also called the Seaside Hotel, but it was just a shadow of the original. The curtain of time had dropped on that one, and modern Hawaii wasn't looking back.