ABOVE: The previous generation of Okinawan restaurateurs in Hawaii, including Fred "Tosh" Kaneshiro, once called the "world's greatest Dodgers fan," opened places like Columbia Inn in 1941, serving American food.

Shari Tamashiro was stunned when she first learned how many Okinawan-owned restaurants there have been in Hawaii. Zippy's, Rainbow Drive-In, Highway Inn, Like Like Drive Inn, Flamingo, Wisteria, Columbia Inn: It's likely at least one of your favorite Honolulu restaurant institutions, past or present, was opened by an Okinawan. When she realized this, Tamashiro, who has a library science degree and is a cybrarian at Kapiolani Community College, began what she often does: She documented everything.

She collected records on the existing restaurants and food businesses. Some notes are practical, like bringing your own pot to Aloha Tofu's factory in the early morning for scoops of warm, soft tofu made hours before. And on Mondays, pre-ordering Okuhara Foods' gobo tempura, available in five-pound bags. (While she's there, she also picks up Okuhara's best seller: "Instead of flowers, I bring my mom imitation crab," she says.) She can tell you that when you ask Jocelyn Kishimoto, owner of Utage restaurant, to notify you when specials like konbu maki or ahi nori tempura are available, she will write down your name and phone number in a black-and-white composition book. And after Tamashiro fielded so many questions about where to get andagi, or Okinawan doughnuts, she published an online list of the nine places, with photos "to show how different the andagi looks." She is also a walking repository of the restaurant families' histories: that the mother of Roy Yamaguchi, one of Hawaii's most renowned chefs and restaurateurs, is Okinawan. That two of the partners in Beer Lab HI, Kevin Teruya and Nicholas Wong, are part Okinawan, and Teruya is the grandson of the founder of Kapiolani Coffee Shop. That the parents of Henry Adaniya of Hank's Haute Dogs were both of Okinawan heritage and ran a concession stand selling hot dogs where the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium is now—his counter is a tribute to them.

This January marks 125 years since the first twenty-six men from Okinawa arrived in Hawaii as contract laborers; now it's estimated that there are fifty thousand Uchinanchu (how Okinawans also identify themselves, as distinct from the Japanese ethnicity) in Hawaii, about 3 percent of the state's population. To help commemorate the 125th anniversary, Tamashiro is part of a project to help Uchinanchu trace their genealogy and share their stories. She quotes the late historian Ronald Takaki, saying, "It's not the stories of presidents and kings that are crying out to be told, it's stories of the common man, the farmers and fishermen, thousands and thousands of stories that make up this community of memory."

A newer generation, such as Chokatsu Tamayose (playing the sanshin), serves Okinawan comfort food at Sunrise Restaurant, which started in 1999.

I meet Tamashiro at one of her favorite Okinawan-owned restaurants, Sunrise Restaurant, which she calls "the gathering place for the Okinawan community." She helped save it during the pandemic. Chokatsu and Tomoko Tamayose own the snug spot just off of Kapahulu Avenue in Honolulu, which Chokatsu started with his aunt in 1999. Regulars come for home-style Okinawan dishes like pig's feet soup and a stir fry of pork and goya (bitter melon). They also know that toward the end of the night, Chokatsu will likely pick up his sanshin, a three-string instrument that he often plucks using a plastic saimin spoon, inspiring diners to their feet for kachashi, an Okinawan folk dance. But in April of 2022, Sunrise was $13,000 behind in rent and facing closure. Tamashiro set up a GoFundMe and, in less than a day, raised $15,000. Donations came from the Okinawan community locally and abroad. One couple in Okinawa, grateful to Chokatsu and Tomoko for taking care of their daughter while she was a student at nearby Kapiolani Community College, donated $5,000. In just a week and a half, $71,000 had poured in. Norman Nakasone, a banker, helped the Tamayoses organize their finances.

To Tamashiro the donations are an example of yuimaru, an Okinawan word meaning community support in times of need. She remembers when she was working on an oral history project with Japanese World War II veterans and they asked her, "'What are the stories that guide you and your generation?' And I was, like, 'George Washington cutting down the cherry tree, saying, 'I cannot lie'?" She decided to choose another story to live by: the pigs from the sea.

World War II had decimated Okinawa—it's estimated that a hundred thousand civilians, about a third of the residents at the time, died in the Battle of Okinawa. The pig population, an important food supply, plummeted from more than one hundred thousand to fewer than eight hundred. The Hawaii Uchinanchu community raised almost $50,000 (about $650,000 in today's dollars) to purchase 550 pigs from the continental United States, and in 1948 seven men from Hawaii helped escort the pigs by ship from Portland to Okinawa. Within four years the pig population was restored to prewar numbers.

"The story reminds us we can accomplish amazing things when we work together," says Tamashiro, whose Instagram handle is @pigsfromthesea. And it's the spirit of yuimaru, she believes, that enabled Okinawans to open so many restaurants—approximately three hundred, primarily in the 1930s to '50s. According to one essay in Uchinanchu: A History of Okinawans in Hawaii, by 1941 approximately 80 percent of Honolulu cafes and eateries were owned by Okinawans. Most, though, are long gone.

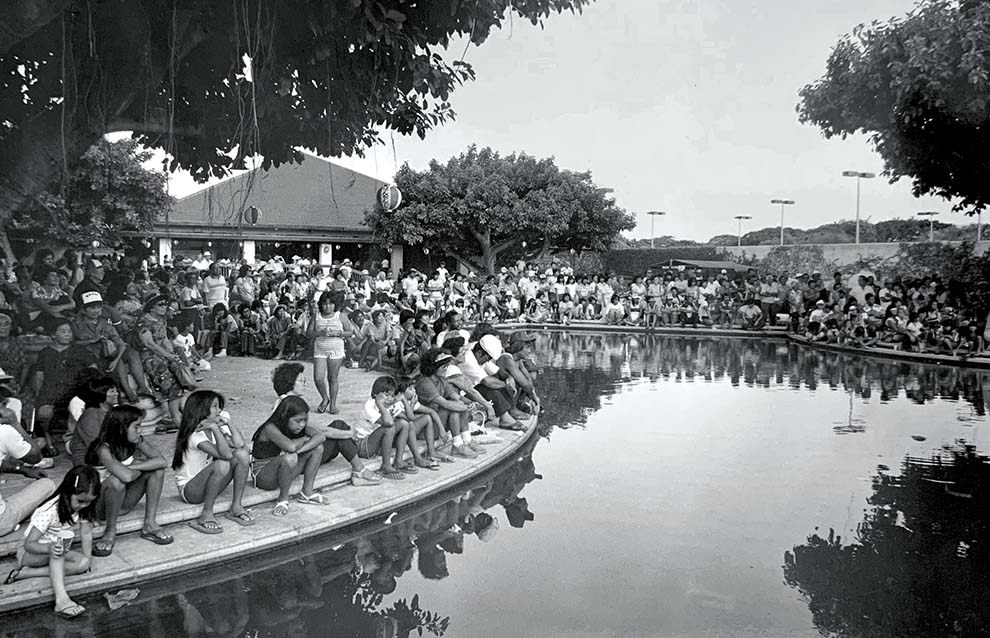

The first Okinawan Festival was held in 1982 at the McCoy Pavilion at Ala Moana Beach Park. It is now considered the largest ethnic festival in Hawaii—a two-day event attracting about fifty thousand visitors.

In 2021, Kevin Teruya, co-owner of the brewery Beer Lab HI, concocted a bitter melon beer to coincide with the Okinawan Festival, an annual event over Labor Day weekend that's billed as Hawaii's largest ethnic festival, attracting about fifty thousand attendees. Until then, "I never thought of my Okinawan side," he says. But when Gene Kaneshiro and Howard Takara, both from restaurant families, learned of Teruya's involvement with the festival, they connected with him "because back in 1983, my grandma died in a house fire, and they had helped with the service," Teruya says. "They said it was a shock to the Okinawan community, about how tragic it was. They recalled it quite vividly. They remembered my grandpa"—who opened Kapiolani Coffee Shop—" and they remembered my grandma, as well as some of my aunties. It opened my eyes as far as the Okinawan side, how much they care about each other. There truly was an Okinawan community of restaurant owners that was very close-knit. I don't think you see that very often, that kind of support. To be honest, I wasn't a very good Okinawan. That was a wake-up—'Whoa, this is important.'"

Kaneshiro and Takara knew it was important—it's why they had started the Hawaii Okinawan Restaurant Project about twenty years earlier, when Kaneshiro's restaurant, Columbia Inn, which his father and uncle opened the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed, closed after six decades in business. The executive director of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaii had approached Kaneshiro to document Columbia Inn's history. "There's a bigger story to this," he told her. "Look at all of the restaurants that were owned and operated by Okinawan families in Hawaii." With support from the JCCH and the Hawaii United Okinawa Association, Kaneshiro and Takara spent a decade gathering stories from the restaurants Okinawans opened in the twentieth century, places named American Cafe, Smile Cafe and Frankie's Cafe. The restaurateurs, anticipating a greater appetite for burgers over bitter melon, created menus featuring American food like hamburger steak and grilled calf's liver. (The restaurants that serve Okinawan food, including Sunrise and Utage, were opened much later, around the turn of the millennium, by a new generation of Okinawan immigrants.)

Pigs from the Sea: During WWII, Okinawa's livestock had been decimated and starvation loomed. Hawaii's Okinawan community raised $50,000 to purchase pigs, which were shipped from Portland to Okinawa on a military vessel, escorted by seven men from Hawaii. A storm damaged the holding pens on the first try, and the ship had to turn back. The second successfully delivered 550 pigs to Okinawa. PHOTOS COURTESY OF JON ITOMURA

From Uchinanchu with ties to the village of Oroku alone, from which Kaneshiro's paternal grandparents and Takara's grandparents on both sides emigrated, they documented seventy-five restaurants. They attributed the restaurant boom to Ushi Takara (no relation to Howard), who opened American Cafe in 1923, and Henry Uyehara, who opened Kewalo Inn in 1930—both Oroku-born restaurateurs who hired and mentored other Oroku immigrants and descendants. One of them, Wallace Teruya, waited tables at Kewalo Inn, where the cooks would butcher frogs from the pond nearby for fried frog legs, before opening his own spot, Times Grill, with his brother Albert in 1938. They closed it a few years after their younger brother, part of the 100th Battalion in World War II, was killed in action in Italy. In 1949 the Teruyas opened the first Times Supermarket, inspired in part by their late brother's dream.

Kaneshiro's own uncle had worked at American Cafe, starting as a janitor and eventually learning all the roles in the restaurant. "Ushi used to recruit all the kids from the plantation to work at his place," Takara says. "Taught them the skills and, when they were ready to go out to do their own, helped them." They borrowed funds through a system called tanomoshi—in which the Uchinanchu pooled money and loaned it out to other members, much like the informal savings and credit associations among Japanese and Chinese immigrants, who couldn't get loans from the traditional banks. "The Italians did it the same way when they came over from Europe to New York; the Irish did it the same way. The Chinese did it the same way in San Francisco and everywhere in the US."

They also supported other Okinawan entrepreneurs. "If everything was equal," says Kaneshiro, "we choose a guy who's Okinawan" for their food suppliers: egg producers, hog farmers, fruit and vegetable distributors. Many Okinawans had turned farming side hustles that they started while on the plantations into bigger businesses—some of them, like Armstrong Produce, Eggs Hawaii and 50th State Poultry, are still among the largest today.

"I think the basic conclusion that we can come to is, here you have a whole bunch of immigrants coming over, and they didn't want to just go and work in a plantation and cut cane and then disappear from life with no history," Kaneshiro says. "I think they came over with the intent of making a living and bringing money and go home as a hero." But finding little money to be made on the plantations, they bet on restaurants as their path to fortune.

About 130,000 andagi, or Okinawan doughnuts, are dropped in oil by hand over the course of the Okinawan Festival. Andagi are also available year-round on Fridays at the Okinawan and Japanese restaurant Utage, as well as at the Aloha Andagi pop-up, which offers them in seasonal flavors like pumpkin spice and strawberry.

Every conversation in Hawaii about Okinawan food seems to begin with pork—like the seven thousand pounds of shoyu (soy sauce) pork Chris Iwamura, the third-generation owner of Rainbow Drive-In, oversaw for the most recent Okinawan Festival. Iwamura manages all of the festival's food production, including pig's feet soup; champuru (stir fry) of luncheon meat, tofu and vegetables; Okinawan soba (thick wheat noodles in a dashi broth)—"basically everything but the andagi," he says. (The andagi batter also coats hot dogs for "andadogs.") It can be hard to reconcile this food with what the rest of the country often associates Okinawa with: a so-called "blue zone," with some of the world's longest-living residents, attributed in part to a diet of primarily homegrown vegetables. But transplanted cultures have a way of morphing into something new. Meanwhile, changes back in Okinawa, including the transition from a sweet potato- to rice-based diet, as well as American occupation and a heavy US military presence after the war, have transformed the way Okinawans eat, giving way to Spam in the champuru and the ubiquity of "taco rice"—in essence, taco fixings, including seasoned ground beef, shredded cheese and lettuce over rice.

The US military also changed what Iwamura's grandfather knew to cook: Seiju Ifuku had served in the famed 100th Battalion during WWII and cooked while on duty, learning recipes that would inform his menu of chili and hamburgers when he opened Rainbow Drive-In in 1961. But if Ifuku collected American recipes for his restaurant, at home he collected Okinawan culture. He had amassed so many antiques—pottery, paintings, scrolls, stamps—that when he donated them to the museum in his hometown of Yaese (formerly known as Gushichan), the prefecture created a new museum just to house a portion of the 1,400-piece collection. Iwamura recently visited his grandfather's village for the first time to see the exhibits. (While there, he also saw a memorial dedicated to those killed in WWII, which included his grandfather's two sisters. "It's an interesting story of my grandpa, who was over in France and Italy fighting for the US," Iwamura says, "and part of his family is killed by the US troops on the other side of the world.")

Since the early twentieth century, there have been more than 350 Okinawan-owned restaurants in Hawaii—Rainbow Drive-In, which opened in 1961, is among those that remain, now run by Chris Iwamura. "My grandpa built this whole thing," he says. "The things I have in my life are because of him."

Okinawan culture "was part of my culture, unknowingly," Iwamura says. When he was younger, he hadn't joined Okinawan dance clubs or any of the Hawaii United Okinawa Association's approximately fifty member clubs, most of them organized around Okinawan towns to which their constituents trace their heritage, but he grew up surrounded by his grandfather's collection and music. His grandfather had always told Iwamura "to be proud to be an Okinawan," but he didn't know what that really meant. His grandfather had died when he was in high school, and his parents, part of the postwar generation trying to assimilate in America, did not pass along the culture.

It's only recently that Iwamura has been learning more. "The common misconception is that Okinawans are basically Japanese, but the culture is so much more affected by other cultures in general," he says. When Okinawa was the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, it traded across Asia, particularly with China and countries including Korea, Siam and Vietnam—influences that can be seen in Okinawa's arts and architecture.

The Okinawan Festival, featuring food, dance and music (including this performance by the Ryukyu Sokyoku Koyo Kai Hawaii Shibu), hosted by the Hawaii United Okinawa Association, is one avenue by which Uchinanchu (Okinawans) express their distinct identity and culture. HUOA also participates in the Worldwide Uchinanchu Festival, a gathering of the Uchinanchu diaspora held every five years in Okinawa.

While Okinawa is often described as the Hawaii of Japan, with its warm weather and beaches, the comparison runs deeper. Outside of the Hawaii Okinawa Center in Waipio, built ninety years after the first Okinawan immigrants arrived, a plaque notes some of these similarities: Both are subtropical islands far from their respective mainlands, Japan and the United States; both have "different and unique culture from the mainland"; both "prospered as independent kingdoms" until 1879 for Okinawa and 1898 for Hawaii; both have their own languages, the plaque says, Uchinaaguchi for Okinawa and "pidgin English" for Hawaii. But there are also parallels left unsaid. Both kingdoms were forcibly overthrown and the Native cultures were suppressed, so much so that the Hawaiian language had almost disappeared by 1990—to the point that it's not even acknowledged on the plaque—and only older generations of Okinawans, like Iwamura's grandmother, speak Uchinaaguchi, a language that UNESCO has designated as officially endangered.

But as with Native Hawaiian arts and language, Iwamura is starting to see a rebirth of Okinawan culture. "It's something I'm really interested in, the revival recently," he says. He now serves on the board of the Hawaii United Okinawa Association and sees part of his role as "trying to help push the younger generation to take some pride, ask questions—Where are we from? What's the difference between Okinawan and Japanese?—to keep the culture alive."